THOMPSONLSR couldn't ask for a better team member, patron, or friend than Eric Hoenig.

NEWS

Stay up-to-date with our progress.

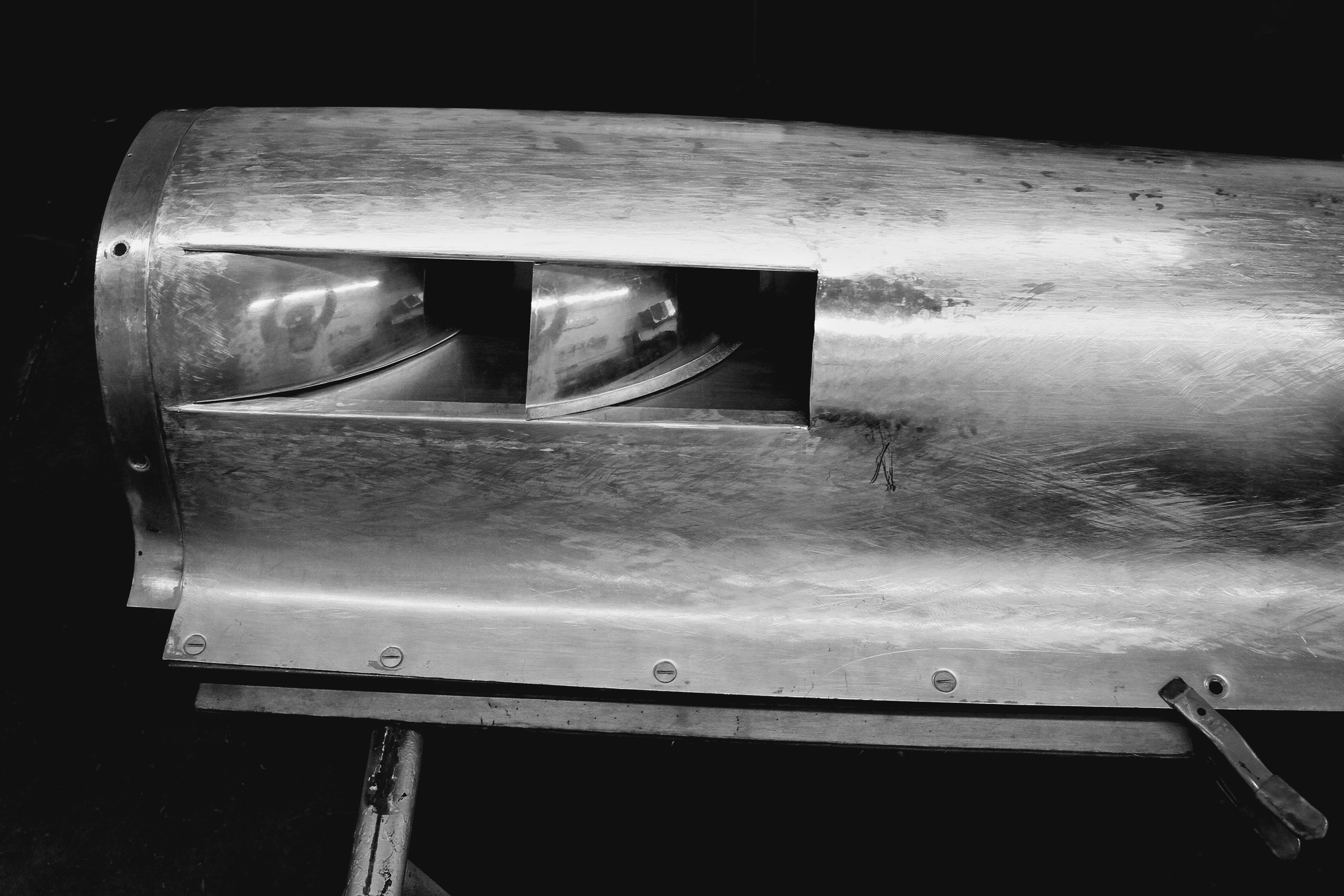

August Photo Update

This month's update is all about air intakes, drive shafts, parachute tubes, and the never ending work on the front end. If you're curious about the changes we've made, our upcoming RACER.com Diary will go into a little bit more detail about the modifications.

RACER.com Diary 18: The Final Grind

I’ll be at the salt this week, but the Challenger II will not be with me. My team and I have been beating ourselves to death trying to finish, but the simple fact is that the streamliner is not done, and I’m unwilling to compromise on any aspect of a vehicle intended to go 450mph with me sitting in it. Doing it right takes precedence over getting it done, which is frustrating but necessary.

The good news is that we’ve most likely found a place where we can test within Orange County, which will save us quite a bit of time and a not insignificant amount of money. We’re a couple months off, but the location will allow us to perform some slow speed tests around 170mph, which is adequate for our aero calculations and will let us function test the new drive train without placing too much stress on it.

Work continues of course, and we’re really making progress on the challenging stuff. Lou is finishing off the front spindles, which will then proceed to heat treat and final machining. The side bells that are bolted to the rear end are now finished. They’re fabricated from 17 individual pieces of hand formed 4130 chromoly, and were welded with high quality heat treatable rod. The welds took over 3.5 hours per side, but I was really pleased with the results. We magna fluxed all of the parts before sending them off for heat treatment, and they ended up perfect.

SK Specialties is just finishing the final machining on the front steering, which was far and away the most difficult modification we made to the streamliner. The front axel, inner and outer u-joints, driver plates and associated parts are all made out of wicked 300M alloy and will be out of heat treat by the time I return from Bonneville. They’ll join the transmission shafts (which are being triple splined) and drive hubs on the way to final grind.

Overall, I’m pleased with our progress and the quality of work we are doing. We’re still raising money via Kickstarter, so if you’re interested, pleased head to thompsonlsr.com and click on the link. See you on the salt!

RACER.com Diary 17: The Mystery Box

In order to promote our Kickstarter campaign, we’ve been doing a lot more press work. For the more technically oriented publications, that means explaining in detail the changes we’ve made to the car. When we get to talking about the rear ends, we inevitably get asked the same question. “Did you say Hadley Box? What’s a Hadley Box?”

That’s a reasonable question. The Challenger II has two engines and is four wheel drive. That means it has duplicated drive trains that are mirror copies of each other. In order to achieve this, we actually had to mount the front engine backwards in the streamliner. The drive trains each have three components--a B&J three speed transmission, a Hadley Box, and a custom built rear end with quick change gears. The functions of the transmission and rear end are obvious. The Hadley Box is a little unusual.

Simply put, the Hadley Boxes mechanically connect the front and rear engines via a three piece drive shaft. The shafts coming off of the engines are mounted at equal but opposite 2.5 degree angles. The middle shaft is perfectly level. This connection allows the engines to remained synchronized during our runs.

Strictly speaking, this system is not mandatory. It’s certainly possible to connect both engines independently to the gas pedal. The Hadley Boxes are a safety feature that we’ve devised in order to keep the engines from running away from each other. For example, should the front engine fail during my run, under normal circumstances the rear engine would keep pushing, potentially resulting in a spin and a crash. With the Hadley boxes, the rear engine will mechanically know that the front engine is locked, the clutch will automatically drop it into neutral, and the rear engine will continue to power both sets of wheels independently to a safe stop.

That’s an extreme example, but the principle of communication holds true in less dire circumstances, including wheel slip, which will greatly impact our ability to make traction. As for the name, the Hadley Boxes are christened after Dave Hadley of SK Specialties, the only person crazy enough to build them.

Thanks for following along. See you next week.

July Photo Update

Let's just be upfront about it. This month's photo update is pure indecent parts porn, courtesy of our fantastic team photographer Holly Martin. Enjoy yourselves responsibly.

Our Kickstarter Project is Now Live!

Our project is officially live! You can see it by going here: http://kck.st/18xEkT4, or just clicking the Kickstarter link in the title bar above. If you can help, we'd be grateful for your contribution. If not, please help spread the word! We're depending on you to get the Challenger II back to the salt. To all of those of you who've gotten us this far, please know that we are extremely grateful. We're gonna make this thing happen!

RACER.com Diary 15: Controlled Slip

I have so much left to learn. That, more than anything, is what rebuilding the Challenger II has taught me. We’re in the middle of finalizing the clutch package, and the whole process has proven to be much more complicated and time consuming than expected. Our setup is primarily a modified version of what you’d find on a Top Fuel dragster. We make a lot of power, and run fuel, so we wanted equipment with proven resiliency under those conditions.

The components themselves are a mix of different materials that you wouldn’t expect to find in the same package. Elements are made from titanium, stainless steel, 4340, 4130, cast iron, and sintered metal (friction material). Bob Brooks of AFT is fabricating the parts. He used to run the piston department of Mickey Thompson Enterprises for my dad back in the 60s, so it’s a real pleasure to have him working with us on this project.

Getting the clutch package to perform effectively on the salt is a tricky process. Our tires are only 4 inches wide, and each one will be allocated almost 1000hp. Getting all of that power to the ground without slipping the tires requires delicate tuning, and probably won’t be perfected until we actually get to Bonneville and tinker with the settings on the salt.

Here’s how it works: As soon as the car moves away from the push truck, I’ll release the clutch. This will happen at a relatively slow speed. Anything over 5mph should be enough. As engine RPM increases, the clutch will slowly lock up automatically. I won’t be moving it in and out during the run. This means, in simplified terms, that the clutch will mechanically perform a controlled slip at slow speeds. This unusual procedure is important for two reasons. First, our engines are dry blocks, so if I back off the throttle to counter wheel spin, the engines will not get enough fuel to cool themselves. Second, we need to make as much speed as possible on the bottom end of the course, so if we’re goosing back and forth or not making traction, I’ll be loosing irreplaceable time.

Work continues! See you next week.

RACER.com Diary 14: The Fastest Guy Out There

In last week’s article I mentioned that Bonneville’s different classes weren’t very meaningful to me, because my foremost goal was to be the fastest piston car on the salt. There isn’t an official designation for that, so I called it “the world’s fastest hotrod”. I stand by what I said, but I probably should have predicted the deluge of questions regarding the actual classifications. For the record, when I run the Challenger II, it will be entered as an AA Fuel Streamliner (FS). That’s not the same category my dad was in when he originally drove the car (he used a supercharger), and my class record is technically lower than his was. But just to emphasize, I don’t really care about winning the class. I want to be the fastest person out there, period.

Just out of curiosity, I counted up all of the classes and engine combinations available in the four-wheeled category. I came up with 825. I did the same for the motorcycles, and came up with an even larger number. That didn’t seem right, so I called up Van Butler, head of bikes for the SCTA, and he confirmed that there were almost 1000 different class combinations. That may sound confusing, but I think it’s a good thing. If you are an enthusiast interested in coming to the salt, you have zero excuses. There is a category ripe for conquest with your name on it. The slowest bike record sits at 19.983 MPH. The fastest is 376 MPH. With four wheel cars, the gamut is even larger. Get to work!

The biggest Bonneville event each year is Speed Week. It gets over 600 individual car and bike entries, and is the one that you should attend if you are interested in getting a taste of the salt’s unique culture. There are a few other smaller events during the season, but I’m primarily interested in Cook’s Shootout, which is limited to 8 vehicles, and tends to be populated by very fast streamliners. It’s the only FIA sanctioned event, and the only time I can qualify for an FIA record.

Thank you for all of your questions. Feel free to keep them coming in. See you next week.

June Photo Update

RACER.com Diary 13: 400mph in a Piston Powered Car

How hard is it to go over 400 MPH in a piston powered car? Well, since 1947, only 11 people have managed to do it. That is, for reference, one less than the number of people who have walked on the moon. But things are heating up. For 52 years, the overall record grew by only 8 MPH. Last year, the Speed Demon exceeded that mark by almost a factor of three, and bumped it by a whole 22 MPH. The Treit & Davenport car, a perennial favorite, is running for the first time after 13 years of development. This year, Bonneville will host the largest gathering of 400 MPH+ streamliners in history, and will proffer the most exciting series of salt events in decades.

Most of those vehicles will be competing in different classes, but to my way of thinking, there is only one real record, and that belongs to the fastest overall piston powered car. There isn’t a specific name for that, but I’ve taken to calling it The World’s Fastest Hot Rod. There are somewhere between 6-8 vehicles with a shot at that title, and I believe that the Challenger II is one of them.

With that said, jumping in the cockpit and mashing the gas tomorrow would be foolish, no matter how badly I want it. Most of the other LSR cars I mentioned were running for years before they cracked the 400 MPH barrier, let alone challenged the record. Sneaking up on the big number has been the modus operandi of the most successful attempts. The team here at THOMPSONLSR has been working like crazy trying to make Speed Week in August. Right now, that date is looking unrealistic given the amount of testing I want to do. There isn’t any room for mistakes at these speeds, so we’ll be trying for runs at the World Finals in October. My current goal for this year, frustrating as it is, will be to make sure that all the functions and safety mechanisms are up to snuff before I gas it.

See you next week.